SERIES FRONTRUNNERS & FRONTIER EXPLORERS - EPISODE 1

IN CONVERSATION WITH JOURNALIST AND HISTORIAN SANDER HEIJNE

How do experts view entrepreneurship in times of transition? Trailblazers talks to frontrunners and frontier explorers to find out. The first guest is journalist and historian Sander Heijne, author of Phantom Growth and known for the podcasts BV Nederland and the Ommezwaai. He tells us about pitfalls from the past, how they affect the present and what is needed to break them in the future. What role should the collective social interest play in business models? And where does this cold feet among larger companies come from when it comes to inclusion and sustainability goals?

READ THE FULL INTERVIEW

By writing your book Phantom Growth you put the Netherlands on edge when it comes to economic inequality. You then continued the debate with, among others, your podcasts BV Nederland and the Ommezwaai, in which you explore what organizations can do to accelerate the fight against climate change. What do you hope to change with your work?

"I hope to contribute to a tilting debate that leads to us no longer focusing only on money and the growth of the economy, but looking at: how do we keep a society together? How do we ensure that everyone can keep up? I think we have spent the last 30, 40 years moulding everyone into the mantra that things have to get bigger, things have to grow. Whether it is within companies, governments, or even within educational institutions But we are on a planet that is not getting bigger. Our resources are not increasing in size. So it's mathematically impossible. And then if we look at why we once embraced that growth mantra, it was to very specifically solve a few problems that were very obvious about 80 years ago, but now are not really at all. For example, we now produce more food than is good for the world's population. We see how obesity is on the rise. There are endless examples where you can see that this growth is actually standing in the way of a good society. So until we are able to decouple that, we are going to have a very bleak future."

Why is it that we have come to find profit maximisation so commonplace? How can such a flaw affect our economic system so fundamentally?

"First, you can ask whether they are contraction errors or whether the system is more or less deliberately put together. If you look at the big turnaround after World War II, for 30 years there was pretty broad social consensus of, 'we need to make welfare states, where everyone can get along.' That was the big political plan across Europe and also in North America. Everyone was in agreement. At some point, there was a clear lobby from rich families to be able to make more profits. And from there, a system of thought was introduced: 'trickle down economics'. People thought: economic growth has led to a lot of prosperity for all people, so we need to make it easier and faster for that economy to grow. And we do that by making companies make more profits. How can you make companies make more profits? By taking away all kinds of legislation. So for instance by not raising minimum wages anymore, or what happened in the Netherlands, lowering them. Or by making employment contracts less secure and abolishing all kinds of social securities. That leads to lower costs for companies, making them more profitable. But at the same time, that social legislation was once in place to provide people with livelihood security. So you might wonder whether it was really a contraction, or whether there was just a lobby that won out and had an identifiable interest in doing so itself."

"ENTREPRENEURS SHOULD START THINKING ABOUT HOW TO SCREW TOGETHER MODELS WHERE WE DON'T JUST THINK ABOUT OUR OWN PROFIT INTERESTS, BUT WHERE WE THINK ABOUT THE WHOLE COLLECTIVE SOCIAL INTEREST OF A SUSTAINABLE, SOCIAL WORLD, WHERE WE CAN MOVE FORWARD TOGETHER. AND YOU DON'T LEARN THAT IN BUSINESS SCHOOLS RIGHT NOW." - SANDER HEIJNE

How does this focus on profit work through in the chains and what consequences do you see?

"From the perspective of making more profit, companies have started looking at their chains. So a company like Philips used to do everything itself, like making televisions, but also producing the cardboard for packaging and cleaning the factory. If there was bargaining in the sales department, everyone benefited from a better collective agreement. From the 1980s, they started outsourcing more and more and buying cheaply from suppliers all over the world. If you no longer had to clean your own business, you would choose the very cheapest cleaning company that could do it for you. In the end, all they have left is their label, the Philips brand. They stick their name on it and they get money for that. What you see is that we have built a kind of galaxy, where the multinational has control over marketing and sales. They can put the products away well, and everything they then need to make the products, they try to buy as cheaply as possible.

If the workers of those suppliers start asking for more money or better working conditions, that company runs the risk of becoming too expensive and losing the contract to another company. That a company in Vietnam, for example, loses the contract to a company in Bangladesh. That is a market, where it is actually almost impossible for working people to ask for wage increases or better working conditions anymore. I think that is a finite strategy. In the short term, it has brought a lot of profits for companies; profitability has tripled since the 1980s. But in the long term, you create such a divide in society, where the majority of people can no longer keep up. I think that's a big risk to holding societies together. I think that's the bigger problem we need to see addressed right now."

What can companies do to break this system?

"When we look at the role of companies on, for example, promoting sustainability, we see that our economy is naturally shaped to a large extent. Whether it's about carbon emissions or how we treat employees socially; ultimately, companies have a key role in that. And as long as companies are run by people who can only express your success in growth terms, then you make short-term choices and it can be at the expense of the people who work for you. It can come at the expense of the climate. Ultimately, if you think: what problem does it solve to keep making profits? That you get richer and richer, but your children won't have a liveable planet any more, then you can ask yourself whether that is still the right parameter to steer on. I hope companies and executives will start showing that they can change things from within the established companies. Entrepreneurs should start thinking about how to screw together models in which we don't just think about our own profit interests, but in which we think about the whole collective social interest of a sustainable, social world, in which we can move forward together. And you don't learn that in business schools at the moment."

What do you think should be taught in business schools? What skills should an entrepreneur of tomorrow develop?

I think the skills are not much different than for a classic profit-driven entrepreneur. You have to think carefully about a product or service, there has to be demand for it and it has to contribute something. Only the ultimate goal doesn't have to be to optimise profits in your spreadsheet. The goal should be that you just get something done for all stakeholders. There are not that many people who are really good at business, but the people who are good at business have a social responsibility to look beyond their own interest. And that is what you would want. If you ask what skill they need, I say: responsibility. A sense of duty, that you are not just doing it for yourself. I have spoken the Ommezwaai to a number of CEOs for The Turnaround who have decided to change course. And the nice thing is, everyone who has finally taken the plunge really enjoys talking about it. They actually feel: I'm doing something right, aren't I? They feel very liberated when they suddenly take into account all kinds of interests that actually make it so that their Wikipedia page might soon say: he/she/they helped keep the world livable. People keep each other trapped in an old narrative that change is difficult or can't be done. But then I think: why not actually? Maybe you are not the right person if you can't do it. You're at a company somewhere, but if you think it can't do what we need, why are you there? I think those are triggers that can make us actually change. Because we pretty much know what we need to do. It's not rocket science anymore."

Do you have any tips for professionals who also want to do better?

"Well, first of all: just do it if you want to. Take that step. It's a lot of fun. And if you find it too scary or too exciting, just go and talk to some entrepreneurs who have made the step. I was with an organic arable farmer who had just made that step. And he said that the deciding factor for him was that he had seen from other arable farmers that it was possible to go organic. He had just engaged in conversation and asked questions like: what do you encounter? How should you do it? Can I make enough sales and profit to feed my family? And as they started talking to each other, he suddenly saw: hey, all those arguments against doing it, they actually all turned out to be overcome. So he did it. Now he finds out that you can also make a good living with a much more nature-inclusive way of farming. He literally said, 'yes, I am a farmer. I have to see with another farmer that 'it can be done.' You just have to see it, that you can have a nice life and have a good business. And that on top of that, there is also a lot more gratitude around you because you are doing something for others."

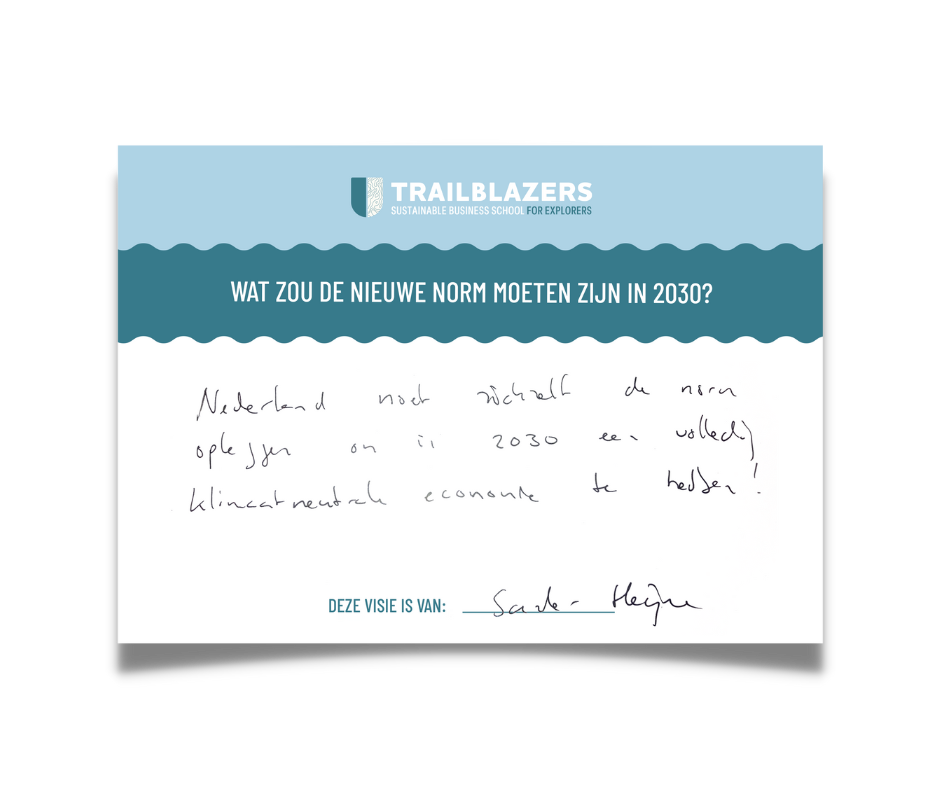

According to Sander Heijne, the new standard for 2030 should be:

"The Netherlands must set itself the standard of having a completely climate-neutral economy by 2030!"